Hard-line Iranian presidential candidate Saeed Jalili may have been Tehran’s top nuclear negotiator for years, but he won no plaudits from Western diplomats sitting across the table as he repeatedly lectured them on everything while offering nothing.

“As the weaving of Iranian carpets progresses in millimeter, precise, delicate and durable manner, God willing, this diplomatic process will also proceed in the same way,” Jalili said then.

Those hours of lecturing in 2008 stalled talks as hard-line President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei advanced the country’s nuclear program. That put pressure on the West that eventually eased with Iran’s 2015 nuclear deal with world powers, which lifted sanctions on the Islamic Republic.

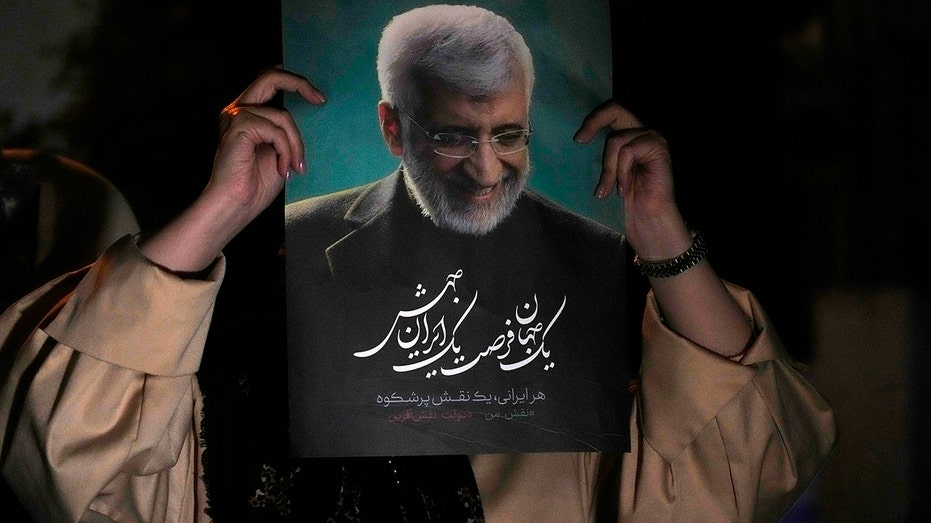

Now Jalili, 58, stands on the precipice of being elected as Iran’s next president as he faces a runoff election Friday against the little-known reformist Masoud Pezeshkian, a heart surgeon. With Iran’s nuclear program enriching uranium at levels near-weapons grade, a win by Jalili may again see already-stalled negotiations freeze.

Meanwhile, Jalili’s own hard-line vision for Iran — derided by opponents as being in the style of the Taliban — potentially risks inflaming a public still angry after the bloody security force crackdown that followed the demonstrations over the 2022 death of Mahsa Amini. She died in police custody after she was detained over allegedly improperly wearing the mandatory headscarf, or hijab.

Jalili, known for his shock of white hair and beard, is known as the “Living Martyr” after losing his right leg in combat at the age of 21 during the 1980s Iran-Iraq war. He was born Sept. 6, 1965, in the Shiite holy city of Mashhad, his Kurdish father a French teacher and a school principal and his mother an Azeri.

Jalili worked as a university professor with a doctorate before joining Iran’s Foreign Ministry, working his way up to a top position before joining Iran’s Supreme National Security Council and becoming the country’s top nuclear negotiator under Ahmadinejad from 2007 to 2013.

He made an impression immediately on his Western counterparts, with then-negotiator, now-CIA director William Burns calling him “a true believer in the Iranian Revolution.”

“He could be stupefyingly opaque when he wanted to avoid straight answers, and this was certainly one of those occasions,” Burns recalled in one meeting. “He mentioned at one point that he still lectured part-time at Tehran University. I did not envy his students.”

An anonymous French diplomat quoted at the time referred to one round of Jalili’s negotiations as a “disaster.”

Another European Union diplomat offered a similar assessment in a 2008 U.S. diplomatic cable published by WikiLeaks.

“An EU official who attended Jalili’s private and public meetings that day was struck by his seeming inability or unwillingness to deviate from the same presentation or provide nuance, calling him ‘a true product of the Iranian Revolution,'” the cable said, not naming the diplomat.

Jalili later would be replaced after he came in a distant third in Iran’s 2013 presidential election to the relatively moderate cleric Hassan Rouhani, himself a former nuclear negotiator. Rouhani’s administration would secure the 2015 nuclear deal, which saw Iran drastically reduce the size and purity of its stockpile of enriched uranium in exchange for the lifting of economic sanctions.

Jalili strongly opposed the deal and formed what he described as a “shadow government” during the Rouhani years to try to undercut his efforts. Jalili also was endorsed in his 2013 run by the late hard-line Ayatollah Mohammad Taghi Mesbah Yazdi, who once wrote that Iran should not deprive itself of the right to produce “special weapons” — a veiled reference to nuclear weapons.

Iran long has insisted its nuclear program is for peaceful purposes.

However, U.N. inspectors and Western nations say Iran had an organized military nuclear program until 2003. In recent months, Iranian officials have increasingly made threats about Iran’s ability to build a bomb if it wanted as it enriches uranium to 60% purity, a short, technical step to weapons-grade levels of 90%.

Meanwhile, advocates for Pezeshkian have described Jalili as potentially bringing hard-line policies akin to the Taliban if he’s elected, something Jalili acknowledged in passing.

“Before the election results were even announced, we called 10 million or 9 million people Taliban?” Jalili said at a recent debate, referring to reformists’ criticism of his policies. “Does this help?”

Jalili hasn’t offered any real comment on how he’d handle the ongoing dispute over the hijab in Iranian society. But those in Jalili’s campaign have been much more direct — calling for stricter punishment against those refusing to wear the mandatory headscarf. One once referred to uncovered women as being worse than a “whore.” Yet during his campaign, Jalili has been vague about how he’d enforce the law and has even posed for a selfie with a woman with a loose hijab, a moment captured in a news photo.

Jalili also has been endorsed by another fundamentalist ayatollah, Mohammad Mehdi Mirbagheri, who belongs to the Front of Islamic Revolution Stability, the far-right edge of hard-liners in the nation. The group, which backs Jalili, was behind a bill passed by Iran’s parliament that could impose 10-year prison sentences for hijab violations. It has yet to be approved by the country’s Guardian Council, a panel of clerics and jurists ultimately overseen by Khamenei.

“They want blocking and closures in everything, no matter the field,” political analyst Mehrdad Khadir told The Associated Press. “It’s the same when it comes to the issue of women, internet or any other issue.”